More Than a Trend: The History of Ube and What It Means to the Filipino People

In recent years, ube has taken the internet by storm with its vibrant purple hue seen in ice cream to donuts to cocktails. But this purple yam has been a cultural staple in Filipino cuisine for more than 400 years.

UBE, (pronounced OO-beh), a sweet purple yam native to the Philippines, has gained increasing popularity over the last few years. Social media posts about its aesthetically-pleasing purple hue and endless iterations in baked goods has helped push it to the American mainstream, going as far as gold-covered ube donuts being sold for $100 per donut.

While many Filipino pastry chefs have led the forefront of these desserts, ube, like an overnight celebrity, has suffered from the effects of fame, leading much of its livelihood to be taken out of context. The discourse being, why is ube suddenly “trendy” when it has been a staple in Filipino cuisine for over 400 years? Who gets to assert its “discovery” in order to be accepted by the American mainstream? And why is ube being reduced to its “eye-catching” purple hue, rather than its deep cultural significance and importance to the Filipino people?

Over time, ube has gotten lost in the cultural chaos of Instagram feeds, and presented in a language of “discovery” by the internet.

I initially wasn’t bothered by ube’s newfound fame. I was actually happy that people were finally noticing desserts that I grew up eating. And I Ioved that more Fil-Am pastry chefs were creating their own spin to ube classics and that these treats were more accessible to me than ever before. Yes, they were all incredibly photo-worthy, and I allowed myself to partake in the hype because I was Filipino - with all the ube I ate growing up in the Philippines, it’s pretty much in my blood.

Yet, if I’m being completely honest, I had no idea about this beloved purple yam’s history and wide-ranging varieties. Even as a Filipino-American, the context and meaning of ube’s origins were lost on me. Maybe I never thought any deeper about it because it was just part of my culture, of my normal.

But in gearing up for this year’s YUM YAMS, San Francisco’s Ube Festival in SOMA Pilipinas, I wanted to learn more about my roots and understand the true beauty of ube - outside of all the hype.

Here’s a breakdown of what I learned:

ORIGINS

The first Tagalog and Spanish dictionary published in 1613 mentioned ube (or uvi) as a type of camote (sweet potato) that belonged to the Convolvulaceae family. Later on, it was classified a yam and part of the Dioscorea family.

Dioscorea alata is the plant’s scientific name.

Ube Jalea/Halaya (ube jam) is the most common and simplest way to consume ube, but there is no known history as to when Filipinos started to create ube into ube halaya.

Fresh milk from carabao (a water buffalo native to the Philippines) was originally used for ube jalea. But with the arrival of Americans in the Philippines in 1898, evaporated milk and condensed milk replaced it. This change in dairy allowed for ease of accessibility and cooking process.

Ensaymada is a Filipino sweet pastry that takes on the form of a fluffy, light brioche bread - a common variation has grated cheese on top. The pastry originates from the Spanish ensaimada.

The use of ube halaya in ensaymada, a sweet dough pastry, was created during Spaniard colonization.

The evolution of ube and ube jalea demonstrates the history of Spanish and American occupation in the Philippines. Yet, like Filipino adobo, ube’s adaptation over time shows how Filipinos have taken different influences and created foods that are uniquely our own.

BENEFITS

Ube is a healthier alternative to regular yams due to having more antioxidants.

According to a study conducted at Kansas University, ube is said to help prevent DNA damage, cardiovascular diseases, and some cancers.

The purple yams also contain Vitamin A, Vitamin C, Vitamin E, and high levels of potassium. Due to its high fiber content, ube also fosters a good environment for probiotic bacteria.

Its deep purple color means that it contains lots of anthocyanins – a chemical that helps reverse cognitive and motor function decline.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF UBE:

Kinampay is one of Bohol’s special food crops - it is seen as sacred to the region due to its role in helping Boholanos survive during wartime and droughts. Photo courtesy of CNN Philippines/Gabby Cantero.

Ube can be planted anywhere in the Philippines. That’s why there are many existing types and regional varieties.

The three varieties as recommended and approved by the National Seed Industry Council are:

Basco ubi (whose cortex has a white-purplish tinge)

Zambales ubi (purple cortex)

Leyte ubi (cream to pink cortex with white flesh)

The original variety is called kinampay, known for its sweet aroma and taste, dubbed as the “queen of Philippine yams.”

Ube can be found in 3 different forms:

A dehydrated powder - made from ube that is dried then pulverized.

An extract - acts as food coloring but also has ube flavor.

A jam/paste - this is the most commonly sold form of ube as it is perfect for use in baked goods.

GROWING AND COOKING UBE

Growing ube is fairly simple as it can withstand adverse conditions, such as drought and risks of pest infestations.

Bohol reigns as the top ube producing province in the Philippines, accounting for 35% of the country’s overall production in 2019.

Ube is usually used in Filipino sweets, like Halo-Halo, bread, ice cream, flan, cookies - the list can go on!

Ube Area, one of our vendors at this year’s YUM YAMS, makes all the ube goodies one can dream of: rice crispies, crinkle cookies, cake truffles, bars, and more.

Ube halaya is traditionally prepared by boiling and mashing the tubers, then stirring them in a saucepan with sweetened milk and butter until the mixture becomes a thick paste.

Ube can be paired with many other ingredients because its starchy texture allows it to easily absorb different aromas. That’s why there’s lots of ube experimentation going on nowadays!

UBE VS. TARO

Taloa’s Bakery, a Filipino and Samoan fusion shop (and one of our YUM YAMS vendors) made this venn diagram to spread awareness of Taro and Ube’s differences.

Ube is vibrantly purple, while taro is typically white on the inside, but it can turn purple after cooking.

Ube is in the Dioscorea family, while taro is in Araceaa.

Taro is called gabi in Tagalog.

Both ube and taro are grown in the Philippines, but ube is commonly used in sweet treats, while taro is used in more savory Filipino dishes, like Laing and Sinigang.

During my research, I found that Jeremy Villanueva, executive chef at Romulo Café, an award-winning Filipino restaurant in London, said it best:

“[Ube] is not just a gimmick of something purple. There's a soul to its consumption. It's part of the culture, it's part of our heritage. Ube [isn’t] a fad. Even if it passes, it will still be part of our culture.”

Despite all the articles and videos I went through about everything ube, I feel as though I’m barely scratching the surface of what this iconic purple yam means to Filipino cuisine. There’s so many variations and experimentations of ube out there, a sign of its ever-evolving, ever-adaptable quality.

As its context and significance continues to shape in my mind, I’m just proud to know that ube is and will always be part of Filipino culture.

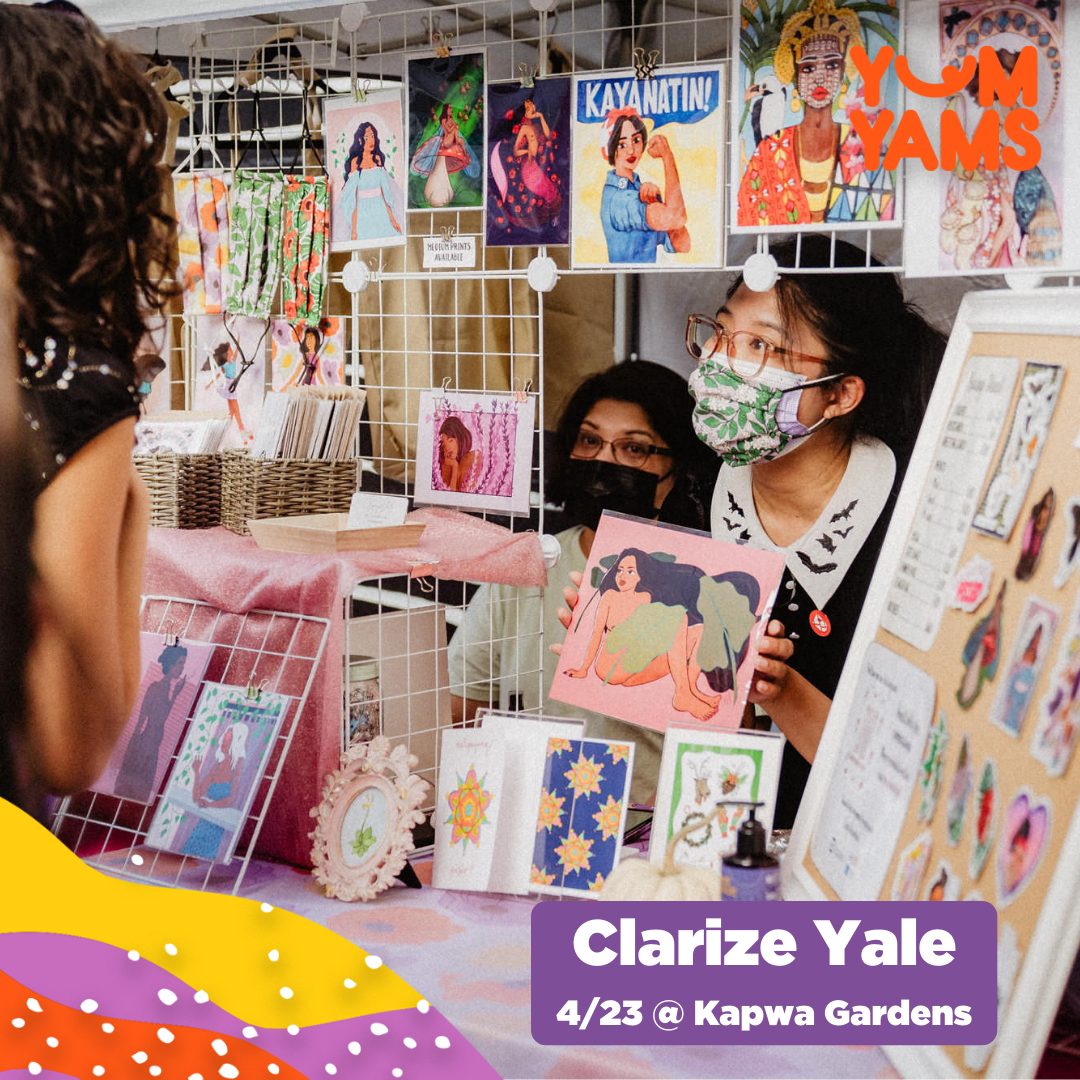

Can’t get enough of ube? Come celebrate all things ube at YUM YAMS, our very own Ube Festival in SOMA Pilipinas on SATURDAY, APRIL 23. Grab your tickets now - before they sell out!

A LOOK AT SOME OF OUR VENDORS

Be sure to follow us @kapwagardens and subscribe to our newsletter to stay in the loop with upcoming events!